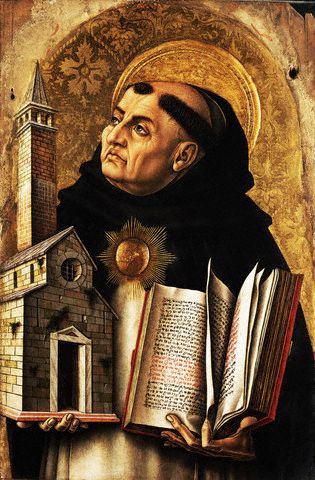

In a conversation with a friend, I will begin to research various theodicies (which seek to explain the paradox of the existence of both God and suffering). Feel free to join the discussion, which will hopefully generate several posts on this blog. For now, what more appropriate place to start than with the greatest theologian the Church has ever produced? And what better format than my favourite (the novel)?

The following quote comes from the book The Quiet Light (Image Books, 1958), a historical novel dealing with the life of St. Thomas Aquinas:

***************************************

Piers hung his head. “You haven’t seen what I have seen, Father Thomas. Madness is ruling in Italy. The big eagle has gone, but the little eagles are almost worse. Wherever you look, you see tears and despair and bloodshed. I felt that my own life was senseless. And I may as well admit it: I am no longer certain that God exists.”

“I needn’t exist,” said Thomas calmly. “You needn’t exist. But God must exist or else nothing else could. You can scarcely doubt your own existence … it’s a violation of the law of contradiction: for if you do not exist, who is it that holds the doubt? So you exist, but not in your own right. You have received existence: from your parents and ancestors, from the air you breathe, the food you take in. A river has received its existence and so have mountains and everything, not only on earth but everywhere in the universe. But if the universe is a system of receivers, there must be a giver. And if the giver has received existence, he is not the giver at all. Therefore the ultimate giver must have existence in His own right, He must be existence and this Giver we call God. Can you contradict that?”

“I cannot contradict it,” said Piers. “But it does not satisfy me. Nor will it satisfy anyone who suffers.”

“Your question, then, is not whether God exists, but why there is suffering. But what is suffering? What is its cause and consequences? It is caused when parts that belong together are separated and prevented from joining each other. And its consequence is pain. A sword cut severs tissues that belong together and thus suffering is caused and leads to pain. Or two people who love each other are separated and prevented from joining each other: suffering is caused and thereby pain.”

…

And he said: “But why must it happen? Why must that which belongs together be separated in life? You explained to me what causes suffering and that pain is its consequence. You did not explain why God permitted the cause.”

“All human suffering,” said Thomas, “goes back to the archetypal suffering … the separation of man from God.”

Piers stopped in his tracks—and only then realized that they had been wandering up and down the garden.

…

Piers began to walk again. After a while he said: “The separation of man from God. That means the story of the Fall in paradise, does it?”

“Yes.”

“It’s so long ago, Father Thomas. What has it to do with you and me.”

“God is beyond time. It was yesterday. It will be tomorrow.”

“I don’t understand that.”

“You will very soon. We are told about the Fall of man in Genesis. The Greeks and other peoples remembered it: they called the time in paradise the ‘golden gage.’ Do you remember the words of the serpent, ‘Eat … and you shall be as God—‘? We ate … and by that act of rebellion cut ourselves off from God. We broke the link between the natural and the supernatural. That was the separation.”

“And were driven out of paradise. And had to die and to suffer. That was God’s answer.”

“No, friend. That was the inevitable consequence of our own act. But God did give an answer and his answer was Christ.”

There was a pause. Piers sihged and in his sigh was England and Foregay and old Father Thorney’s impatient voice,

…

But Thomas said: “Our Lord took upon Himself the total pain of that separation. The union between God and man is the Cross.”

…

“Supernatural life was restored to man,” said Thomas. “And thus God is like the precious soil into which the seed, man, is sown. And the seed branches out into three roots by which it clings to the soil: the roots of faith and hope and charity. And all three are acts of our will—the will to accept the truth as revealed by God—the will to trust the promises of Christ—and the will to see God, the supreme Good. …”

“I think I understand that,” said Piers, “it’s like … like an oath of allegiance to the love of God.”

Once more he saw that irresistible smile that seemed to confer an honourable accompliceship.

“You see now,” said Thomas, “suffering means sharing with Christ. If you love Him … how can you renounce suffering? No lover will renounce the pain of his love.”

“True,” said Piers hoarsely. “True.”

“Man loves so many things,” said Thomas. “Wealth … or power … or a woman. But if you had to name what all men desire, whatever forms their desire may take … what would you say?”

“Happiness,” declared Piers after a short hesitation.

“Yes. Happiness. But what is happiness?”

“I … I don’t know. I know what it is for me. …”

“There is then something you desire more than anything else.”

“Yes. But I shall never have it.”

“And if you had it, you would be happy?”

“Yes, of course. But …”

“But if you had it and so had to fear that it might be taken away from you again—would you still be happy?”

“N-no, I suppose not. Not entirely.”

“Therefore … shall we agree that happinesss is the possession of the desired good … whatever it is … without any fear of losing it?”

“Yes … I think so.”

“But in this life on earth we have not only the fear but the certainty that we shall lose it. For one day we must die. Therefore true happiness … lasting, everlasting happiness cannot be our lot on earth. Nor could it be otherwise. For everlasting happiness is only another name for God.”

Thomas’ eyes shone. “Do you see it now? The urge for everlasting happiness is still in man, in all men. But since the Fall it has been misdirected and like fools we see our happiness in this or that—in the accumulation of gold or of power or in the union with another creature, when in reality it is in God alone. The love of God is the true quest of man. ‘Love and do what thou wilt,’ said St. Augustine. And our Lord said: ‘Seek ye therefore first the kingdom of God and His justice, and all these things shall be added unto you.’”

1 comment:

I just discovered your blog and the excerpt from The Quiet Life you posted and even though it was over a year ago that you posted it I wanted to thank you for it as it helped me immensely. God bless

Post a Comment